I’ve never been much into buying jewelry. However, even I knew that there was one particular purchase that would warrant careful thought and consideration: the diamond engagement ring for my future-fiancee. The diamond industry is more than happy to accommodate the ignorant, but sincere, purchaser. I quickly learned that, to be an informed diamond shopper, I needed to pay attention to “The 4Cs”—cut, color, clarity, and carat-weight; four properties by which I could evaluate these sparkly carbon crystals. I only used them once, and haven’t needed to evaluate diamond quality in over a decade, but for some reason I still remember those catchy “4Cs.”

Here at CodeCarrot, we spend an awful lot of time evaluating code quality. Good developers love to write good code, so naturally they discuss and debate what makes code good. Like evaluating a diamond, the thorough evaluation of code requires the consideration of multiple attributes. But unlike diamonds, there’s no industry association spending the big bucks to help developers remember which attributes to consider.

While the coding community does have a considerable amount of scholarship and industry experience to draw from, it is rarely distilled into pithy mnemonics like the “4Cs”. Of course, you can’t say in a jingle everything that should be said on a topic, but we sure do get a lot of mileage out of the short-hand names we use. When discussing code quality and design, acronyms like DRY, KISS, and YAGNI are used so often that they don’t just speed up our communication, they also influence the evaluations themselves. We come to expect to hear the terse “Keep it DRY” during code review, and from that we learn to factor out unnecessary duplication before we even write it (or at least before we submit it for review).

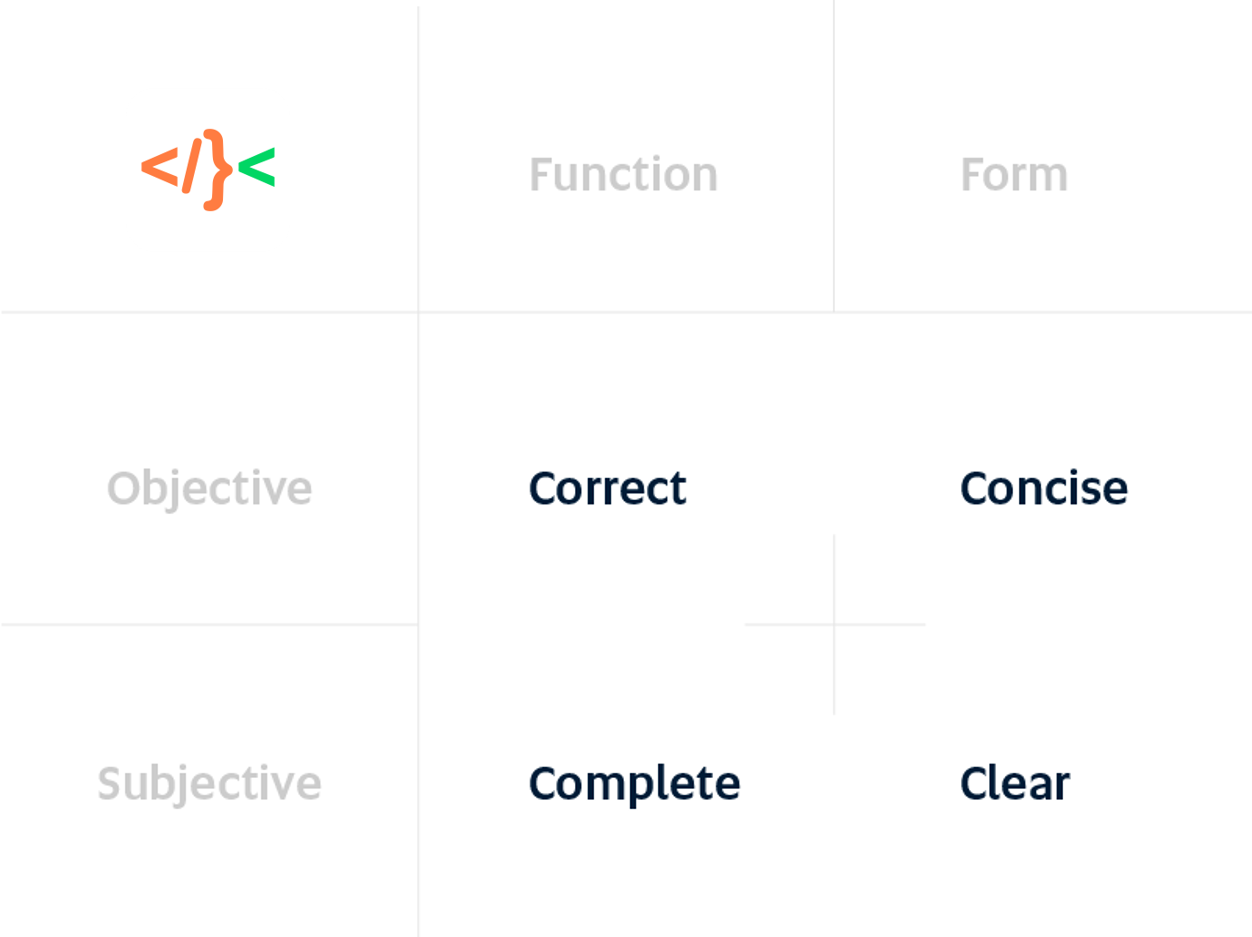

The popular code-quality mnemonics tend to address particular patterns or principles, but I can’t think of any that capture the kind of big-picture checklist of attributes that I actually use when evaluating code quality. The overarching properties of good code are: Correctness, Completeness, Conciseness, and Clarity.

Since Creativity didn’t make the list, I call these the 4Cs of Code Review. It’s easy (and sometimes appropriate) to narrowly focus on one single aspect of code quality, but I prefer to use attributes that encourage the broadest possible evaluation. Therefore, I make sure that the attributes cover the super-categories of design (Form and Function) and of communication (Objective and Subjective).

To begin, I’ll explain the importance of the super-categories and how I use each one.

Both Function and Form

A comprehensive evaluation of code-quality needs to take into consideration both the form and the function of the code. Most developers find it pretty natural to focus on the code’s function: What does this code do? How does it behave? This is taking the computer’s perspective on things, and because the computer has the authoritative interpretation of exactly how that code will function, that’s a pretty important perspective to consider. But it’s not the only one.

Some developers are less inclined to evaluate the code’s form, that is, not only what the code says, but how the code says it. Perhaps because they’ve worked in an environment that didn’t appreciate how form and function are related in software; they were only ever evaluated based on the code’s immediate function. Whatever the reason, I find that developers sometimes need to be told that considering a code’s form is not only allowed, but required.

Form matters because code is meant to be read by other developers. So, we have to take the human perspective on things, as well as the computer’s. What does the code look like? How does it read? What does it imply? What is it similar to? How do I feel about it? In code, form and function are so intimately intertwined that it’s difficult to imagine good code that doesn’t excel in both aspects.

Both Objective and Subjective

While evaluating code, we make both objective and subjective judgments. Objective things can be measured or proven: How fast will this run? Do the tests pass? How many lines of code are in this method? There’s a whole fascinating world of software metrics and static analysis techniques out there. Eventually, however, all of the objective data about your code still boils down to subjective opinion. Are 30 lines too many, or is 300ms too slow?

The subjective analysis depends on our past experiences with code, and on how we perceive the code: Is the code’s intent obvious? Is it clever and elegant, or esoteric and complex? In some ways, the subjective elements are harder to evaluate; or at least harder to agree on. Yet, they are even more important to the art of software engineering than the objective elements, because they are the reason the software is still written by humans. After all, software engineering is as much about the engineer as it is about the code. The things that can be measured objectively are one step away from automation, but the many things that can’t be measured still matter. The subjective value-judgments which shape the code will remain crucial as long as humans are the programmers.

Now that we’ve defined the categories in which code is evaluated, we can consider the 4Cs themselves; Correctness, Completeness, Conciseness, and Clarity. Each virtue describes a different aspect of good code, and understanding them individually is essential to evaluating code and to achieving them in your own code.

Correctness

Before diving into the fuzzier aspects of code evaluation, let’s get the cold, hard facts out of the way. At the end of the day, good code must be correct in the mathematical, verifiable, defect-free, bugless sense. It must always Do The Right Thing. If this is difficult to confirm, it’s usually because the code is unclear, or because the intended function of the code is not well-understood; which means you might need to clarify your specification.

Evaluating correctness is easier said than done. It requires a certain suspicious attitude and a critical eye. This doesn’t come naturally—it must be learned, practiced, and honed.

It’s easy to identify and ask questions to which you don’t know the answers. However the best way I know to learn to evaluate correctness, is asking lots of questions; especially questions to which you think you already know the answers. Doing this takes a healthy amount of self-suspicion, but that is exactly what’s necessary. After all, if you knew the code was correct, you’d be done already. By at least behaving as if you don’t know if the code is correct, or better even, don’t know much at all, you maximize your chances to notice when something is not correct. Looking back over the code, while treating it like suspect work, gives you eyes to see the errors you might otherwise miss.

It helps to have a bag full of “dumb” questions to evaluate correctness. Here are some I use:

- What exactly does this code do?

- Does that agree with the author’s intent, as represented by code comments, commit messages, or other external documentation?

- Is what the author intends self-consistent?

- Does this code actually satisfy the specification?

- Will the tests pass?

- How will the code break? Will it fail gracefully or catastrophically?

- Can this code be misused to produce an unexpected or invalid result?

- Can this code be abused to do something nefarious?

- How will the code behave in all the different contexts where it may run? (e.g. server-side, client-side, backgrounded)

Completeness

Completeness certainly relates to correctness, so you might be tempted to treat completeness as just another component of correctness. Perhaps that’s true in some formal sense, but in the practical evaluation of code quality, completeness deserves its own consideration. Particularly because completeness is not always so straightforward as the black-and-white correctness.

To evaluate if code is complete, we must first identify its intended scope. We must decide, not only if the code correctly does what it does, but also if it accomplishes everything it needs to accomplish. In practice, it’s common to find code that is correct as far as it goes, yet fails to accomplish some portion of what it should. Often, this is simply the author’s failure to imagine the breadth of conditions under which the code may be used. Occasionally, scope is debatable. We may legitimately decide that some “edge” conditions are just not worth handling. For example, we may discover that our multi-tenant web app doesn’t handle cookies correctly when run from a hostname with no top-level domain (e.g. “localhost” instead of “localhost.test”). We don’t like to call these “bugs,” so we call them “limitations,” document them, and live with them.

Sometimes, even when it’s indisputable that our software should correctly handle some “edge” case, it’s not altogether clear whose responsibility that is. The author of the code under evaluation may believe that his code should be able to depend on invariant preconditions that aren’t actually being enforced. For example, an email notifier may assume that form validation has already rejected any email address that would cause a SMTP syntax error. In these cases, once there’s agreement about scope, and you’ve documented the decision, figuring out how to close the completeness gap is usually straightforward.

Incidentally, evaluating completeness can be more difficult for developers who are used to relying more mechanically on TDD. It’s impossible to write tests that exercise non-trivial code in all possible variations. Choosing representative examples in tests is part art. You still have to evaluate the code’s completeness with respect to its scope, not merely with respect to the tested cases.

These are some sample questions to help evaluate completeness:

- Does the code narrowly satisfy a specification which is itself incomplete?

- What cases aren’t handled? (e.g. look for conditionals with no elses)

- What is the code assuming? And should it? (e.g. that time always moves forward? that the entire list of users will fit in RAM?)

- What environmental changes might cause a reasonable assumption to become unreasonable? (e.g. assuming a timely response from a webservice that might go out of business)

Conciseness

Concise code economically communicates the essential function, and is often clearer than less concise code. But, just as some consider completeness merely part of correctness, some consider conciseness as merely a prerequisite to clarity. In reality, clarity and conciseness have both a complementary and competitive relationship. Unclear code is often wordy and repetitive, but overly-verbose code can still be quite clear, despite its length. That doesn’t make it okay. Brevity is a virtue. At the same time, there’s a point where objectively more concise code becomes subjectively less clear. You should strive to find this elusive balance. Don’t sacrifice clarity on the altar of conciseness.

These sample questions can help you evaluate conciseness:

- Is there anything here that can be omitted without reducing any of the other 3 C’s?

- Does the code give the appropriate emphasis, dwelling only on the most important things while breezing over the trivial details?

- Are there idiomatic expressions that are appropriate short-hands for any of this code?

- Are the lengths of variable/method/class names justified by their importance?

Clarity

All code is communication, and all good code is clear communication. Good code clearly communicates its function and intent. Clarity in code has more in common with good old fashioned literary composition than most developers realize. A novel, a magazine article, and a feature branch all are meant to be read and understood; they all string together ideas and concepts to tell a story. They all reuse patterns, derive meaning from context, and imply relationships to their greater environments.

Clarity comes from the top-down (logical sequencing, coherent units of thoughts, familiar structures), as well as from the bottom-up (consistent use of punctuation, choosing meaningful names, precise use of the language’s grammar and syntax).

Writing clear code requires knowing your audience and accommodating your reader. It doesn’t always mean assuming a reader who is completely unaware of the advanced concepts and idioms of your language—that would be like always writing childrens’ books. Neither does it mean always using the most sophisticated expression of thought that you can come up with—that would be like always writing academic papers. Writing with the needs of a representative reader in mind results in clearer code.

Writing clear code is much more difficult than most developers realize, but evaluating code-clarity is easier than most developers realize. If you’re reviewing code in some professional capacity and you’ve put in a reasonable effort to understand it, but you are still lost, or even a little unsure, have the confidence to conclude that it’s not you—it’s the code. Sure, there’s the possibility that you’re just dumb, but I’ve trained an awful lot of developers and read an awful lot of code, and I can confidently say that the odds are pretty good that the code is more obtuse than you are. This even holds true if you are less experienced than the code’s author. Writing clear code doesn’t correlate with programming experience as strongly as you might expect. Trust your gut—if you think it could be clearer, it probably should be.

Here are a few sample questions to help evaluate clarity:

- Does this code do what I thought it did at first glance? If not, why not?

- How long did it take me to really understand this code?

- What’s this going to look like to a casual reader? After two beers? To me in 6 months?

- Does the code really do what it seems to do?

- Does the code contain any pointless innovation, something different from a more common approach, without good reason?

- Does this code inspire confidence? (e.g. with adept use of interfaces and libraries)

- Or does it create doubt? (e.g. with unnecessary double-checking)

- Do the names chosen have any misleading connotations? (e.g. singular vs. plural variable names, method names that could ambiguously be a noun or a verb)

- Are the names as precise as they should be?

- Does the code have an even tone? (e.g. consistently assuming or not assuming familiarity with certain constructs)

Conclusion

So, what help is a long essay when you’re expected to give your teammate’s code some meaningful review? Remember this: a thorough code review means asking lots of questions. You’ll answer most yourself and some you’ll have to ask the author. Follow where the questions lead, and if you get stuck, just return to the 4Cs:

- Is it Correct?

- Is it Complete?

- Is it Concise?

- Is it Clear?

If you’re developing a web or mobile app and need help answering these questions, CodeCarrot might be able to help.

Response to “The 4Cs - A Code Review Mnemonic”